This post continues my three-part exploration of a short Ottoman manuscript text, Risāla fī ithbāt ruʾyat al-nabī yaqaẓatan li-man iṣtafāhu min ʿibādihi al-ṣāliḥīn, by the otherwise obscure scholar Muḥammad b. Aḥmad al-Kūmuljinawī; if you have not already read Part I much of the following will not make sense, so start there then proceed to the following.

In Part I we were introduced to the manuscript as a codicological unit, and reviewed some of the paratextual aspects that appear in this handful of folios. In the remaining pages the same elements continue, plus some additional ones, which we’ll examine before plunging into the main topic of this post, the theological content and the way in which al-Kūmuljinawī drew upon existing authorities, how he might have gone about locating sources, and what we can gather about ‘canonical’ theological authorities in the eighteenth century Ottoman world. Let’s have a look at the second page in the treatise and note the paratextual elements visible there:

First, it’s important to pay attention to things that might otherwise fade into the background: for instance, this manuscript features a frame around the main text, a common feature but not a universal one, bespeaking the refined nature of the manuscript and its intended purpose as a presentation text. More mundanely, the frame neatly demarcates the main text from its marginal apparatus: in the case of this manuscript, primarily comments that are the functional equivalent of footnotes in modern book practice. In the example above, three annotations are visible, all examples of the minhu, ‘from him,’ type of note, placed there by the author of the text (at least in this case- in other cases the provenance of such notes can vary). The notes are linked to particular points in the main text via rubricated letters, very much akin to the footnote, although spatially they are placed more or less proximate to the linked section of main text, and hence in a variety of arrangements- an affordance of handwritten texts that is considerably more of a challenge for typography (though not insurmountable; not a few early Ottoman printed works featured sloping commentary text, though not at varying angles as here).

Nearly all of the minhu comments in this section, save a single (incorrect as it turns out!) translation of an obscure Arabic word into Ottoman Turkish, are in the same hand as the main text, which we’ve every reason to believe is the hand of the author (or, if not in his actual hand, the hand of a scribe to whom he dictated). For more on these notes and their relationship to authorship, manuscript transmission, and so forth, see A Tunç Şen’s ‘Authoring and Publishing in the Age of Manuscripts: the Columbia University Copy of an Ottoman Compendium of Sciences with Marginal Glossing.’

The other paratextual element to notice in this section of the text is the use of red overlining at various points: there is no single modern equivalent for this overlining, as at points it functions like italicizing or bolding, drawing attention to a particular point in the text; at other points it functions somewhat akin to quotation marks, or, at least, the first set of quotation marks. In the example above, the final line is largely overlined, marking out a particular ḥadīth visually from the rest of the text (in Persian texts from this period, switching from nasta’liq to naskh for ḥadīth and Qur’ān did similar visual denotation work). Taken together, all of these paratextual elements- dots, rubricated words and letters, and overlining- aid the reader in navigating and interpreting the text, knowing immediately where cited texts begin, or where important arguments or transitions are located. In my translation below I’ve largely ‘translated’ these elements into modern punctuation; on reflection I think it would be interesting to try and replicate them exactly, and will try to do in the final installment of this series.

I have aimed for a relatively literal translation, while trying to draw out some of the nuance in the usage of technical vocabulary, the most challenging aspect of this text to render in English. I initially tried a two-column display here, but found that it caused a serious error when displayed on the front page of the website, unfortunately, so I have had to drop the marginal notes down to the end of the translated section.

Know that it has been established by definite texts from among the sound and sunna-conforming aḥādith that our lord and master Muḥammad, God bless him and give him peace, is alive in his grave in body and soul, and that he has freedom of action and can go where he wills in the quarters of the earth and in the imaginal realm (al-malakūt). Verily, he—God bless him and give him peace—is [still] in his noble form in which he was before his death, nothing has been changed. And if he, God bless him and give him peace, is hidden from the sight of the likes of us, it is due to the relational distance between us and between his noble person, due to the turbidity of our lower selves due to the passions of the self and their immersion in the attachments to these trifling vain wordly babbles, just as the noble angels are hidden from us even as they are in our very midst.

Now, if God desires to honor anyone with this bodily miracle, He raises the veil and he is able to see him in his true form (this does not entail that the one who so sees him is in the ranks of the Companions in a sharī’a-accordant sense). The generative cause for the obtainment of this vision is his following the sunna in his deeds and words. The more that he strengthens his following [of the sunna] the more resilient will be his personal connection [with Muḥammad], and love [for him] will increase. This is the fundamental root of all union and separation—there are those people who are scarcely ever in a state of separation and those people who are scarcely ever in a state of union [marginal note a.].

It has been established by multiple avenues of transmission that many among the noble saints, God sanctify their inner secrets and pour out blessing upon our hearts from the orients of their lights, see him, upon him be peace and blessing, in waking life, and spiritually benefit from him—that is something that is known to the one who comes to the path of the saintly or who associates with them, such that it becomes akin to necessary knowledge.

Al-Ajhūrī (d. 1655) [marginal note b.] said, ‘The shaykh of our shaykhs, Aḥmad ibn Ḥajar al-Haythamī said that Ibn Abī Jamra [marginal note c.] said that al-Yāfi’ī and al-Bārazī and others from among the community of the saintly pious have said that they have seen the Prophet, God bless him and give him peace, in waking life. And Abū Jamra mentioned that they experienced that in accordance with the transmitted saying, “The one who has seen me in a dream-vision, he will see me in waking life.” Truly, they have seen him in dreams and they have seen him afterwards in waking life, and have asked about various things and he has reported to them concerning those things, and it has turned out as he has related to them.’

The one who denies that, if he is from among those who cast calumny upon the miracles (karāmāt) of the saints—then we have nothing to say to such a one. Otherwise, this [vision] is from among [their miracles], when in the rending of [the] customary [nature of things] there is unveiled to them things in the world above and below.

Al-Fāsī (d. 1698) says in Maṭāli’ al-massarāt [his commentary (sharḥ) on] Dalā’il al-khayrāt: ‘Shaykh Abū ‘Abd Allāh al-Suhaylī [also vocalized as al-Sahlī], God be pleased with him, has said: “In order to affix love of the Prophet in the soul, do not let his noble form be hidden from the eye of insight for a moment—it is the true vision because the vision of sight is due to his conveyance of the true essence of the one who sees to the eye [or essence] of insight, so that in the presence of insight there occurs comprehension regarding the true reality of what is conveyed to [sensory] sight from among the visible things. There is no doubt that ṣalāt upon the Prophet, God bless him and give him peace, if one’s innate disposition (mashrab) is purified, will shed forth its lights and the lower self (nafs) will become a mirror for [Muḥammad’s] form, God bless him and give him peace, and will not be hidden from it. This is true knowledge in which there is no doubt.

“Now, the people are in differing degrees in terms of the impressing of his image, God bless him and give him peace: there is one for whom his noble image, God bless him and give him peace, is not established in his soul except after much meditation, fixation, and contemplative work—these are the weaker of the folk. There is one who finds his noble image affixed within himself during times of remembrance of him, especially while in pious seclusion (al-khalwāt) when the contemplative faculty is fully devoted to the realization of purification, and if it slackens at all [the image] is hidden from him. This is a progression up from the first—this one sees him in a dream-vision in accordance with his perfect form, while the first, if he sees him at all, sees him in something other than perfection of vision. And there is the one who, if he obstructs his eye at all whether waking or sleeping, he sees him with the eye of his perceptive faculty in the midst of every spiritual state. Such ones are the folk of the utmost degrees, those whose hearts have been rendered tranquil through remembrance of God, to the point that their lower selves have risen into the paradises of proximity, and they are rewarded with the wages of those upon whom God bestows blessing from among the prophets, the sincere, the martyrs, and the saints—such ones are excellent companions!

“And from among them [the degrees] there is one that is a higher degree even than this: that is that one see with the eye of his physical head, directly and visually, his perfect form in the world of sensation, especially during times of dhikr. That is because if the spirits obtain a profound harmony through abundance of ṣalāt upon him, then his noble spirit appears in visible form in his pure body, until the one who prays gazes upon him, at one moment with his physical eyes, at another with his interior comprehension, in accord with the power of his harmonization of the spirits or his weakness, as the vision of the insightful faculty is stronger than the vision of sight.” Attend to his statement, “then his noble spirit appears in visible form in his pure body, until the one who prays gazes upon him”: it is related to what has been established concerning more than one of the saints concerning the waking vision of the Prophet, God bless him and give him peace.’ So conclude the words of al-Fāsī.

Ḥujjat al-Islām al-Ghazālī said in his Kitāb al-munqidh min al-ḍalāl, ‘And they’—meaning the lords of hearts—‘witness the angels and the spirits of the Prophets in waking life and hear their voices and obtain from them spiritual benefit.’

And Shaykh Sirāj al-Dīn ibn al-Mulaqqin (d. 1401) said in his Ṭabaqāt al-‘awliyā’ that the saintly Shaykh ‘Abd al-Qādir al-Gilānī, God sanctify his honored inner secret, said: ‘I saw the Messenger of God, God bless him and give him peace, before noon prayers, and he said to me, “O my son, why do you not speak?” I answered, “O my father, I am a non-Arabic speaker, how can I speak in the elegant language of Baghdad?” He said, “Open your mouth!” So I opened it, then he inserted [his saliva] [marginal note d.] in it seven times, and said to me, “Speak to the people and call them to the way of your Lord with wisdom and sound exhortation!” Then I prayed the noon prayer, sat down, and many people gathered around me, but words failed [marginal note e.] me in the moment—then I saw ’Alī, God be pleased with him, standing before me, and he said to me, “O my son, why do you not saying anything?” I replied, “Words have failed me!” Then he said, “Open you mouth,” so I opened it, and spit therein six times and I said to him, “Why did you not continue to seven?” He replied, “Out of concern for good manners (adab) with the Messenger of God, God bless him and give him peace!” Then he disappeared from my sight. Then I said, “The pearl diver of the contemplative faculty dives into the sea of the heart seeking pearls of gnosis, then bears them out to the shore of the breast, the he calls out to the broker, the interpreter of the tongue…” and so on.’

[marginal note a.]: Shaykh Akmal al-Dīn al-Pāpardī (?) al-Ḥanafī says in his Sharḥ al-Mushāriq concerning the hadith ‘the one who has seen me…’: Union is between two people waking and sleeping, due to the occurrence of the existence of union; there are five roots to it: entirety of sharing in essence, or in attribute and on beyond that, or in spiritual state (ḥāl) and on beyond that, or in deeds, or in ranks; and everything that is related between two things or multiple things has to do with these five. One’s power is reckoned in accordance with the existence of difference and his weakness, he increases or decreases it thereby. It has also been strengthened by its opposite: for love is made more powerful when two people or scarcely ever parted, or by its opposite [i.e. scarcely ever united]. And the one who realizes the five fundaments and firmly establishes his relationship between himself and the perfected departed spirits is united with them whenever he wishes.’ Al-Fāsī has [also] transmitted thusly in his Maṭāli’ al-massarāt sharḥ Dalā’il al-khayrāt.

[marginal note b.]: the commentator on Sīr Alifiyya al-’Irāqī.

[marginal note c.]: the commentaror on Mukhtaṣir al-Bukhārī]

[marginal note d.]: al-taghall: akin to spitting (al-bazq), but is less than it—in sequence, spitting, inserting saliva, expectoration, breathing into. – [al]-Qāmūs [al-muḥīṭ]

[marginal note e.]: al-artijāj: [in Ottoman Turkish]: to be prevented

There is a lot that we could unpack in this section, given that understanding the various elements entails a broad comprehension of medieval and early modern Islam and the technical vocabularies that had emerged for various disciplines long before. The core ideas that al-Kūmuljinawī is defending are 1) the continued physical vitality of the Prophet in the tomb and, at much greater length as it was much more contested, 2) the possibility that certain contemporary humans can develop the spiritual acuity whereby they may behold the Prophet present before them in waking life, in some sense- the language is I think somewhat opaque on this end- actually physically present. The undercurrent of all his arguments is the existence and validity of saintly authority, itself predicated on the continued existence of saints and saintly miracles. While he suggests quite baldly that he will have no brook with the ‘deniers’ of the saints, much of this treatise in fact functions as a defense of saintly authority, since interaction with the Prophet in waking life was a not infrequent means whereby early modern Muslim saints built their own status and authority as Friends of God. As such it was a real flashpoint in the debates- which could turn quite raucous and even violent- between the ‘friends of the Friends of God’ and their ‘puritanical’ opponents such as the Kadızadelis (though most opponents of saintly authority lacked any sort of organization or wider affiliation; the Wahhabi movement would only emerge onto the broader Ottoman scene later). These were not idle debates for the sake of splitting theological hairs. Instead, they reached into the very foundations of Ottoman Islamic society and the question of how Islam should be lived in daily life, with the resulting visions often diverging quite dramatically in terms of everyday applications.

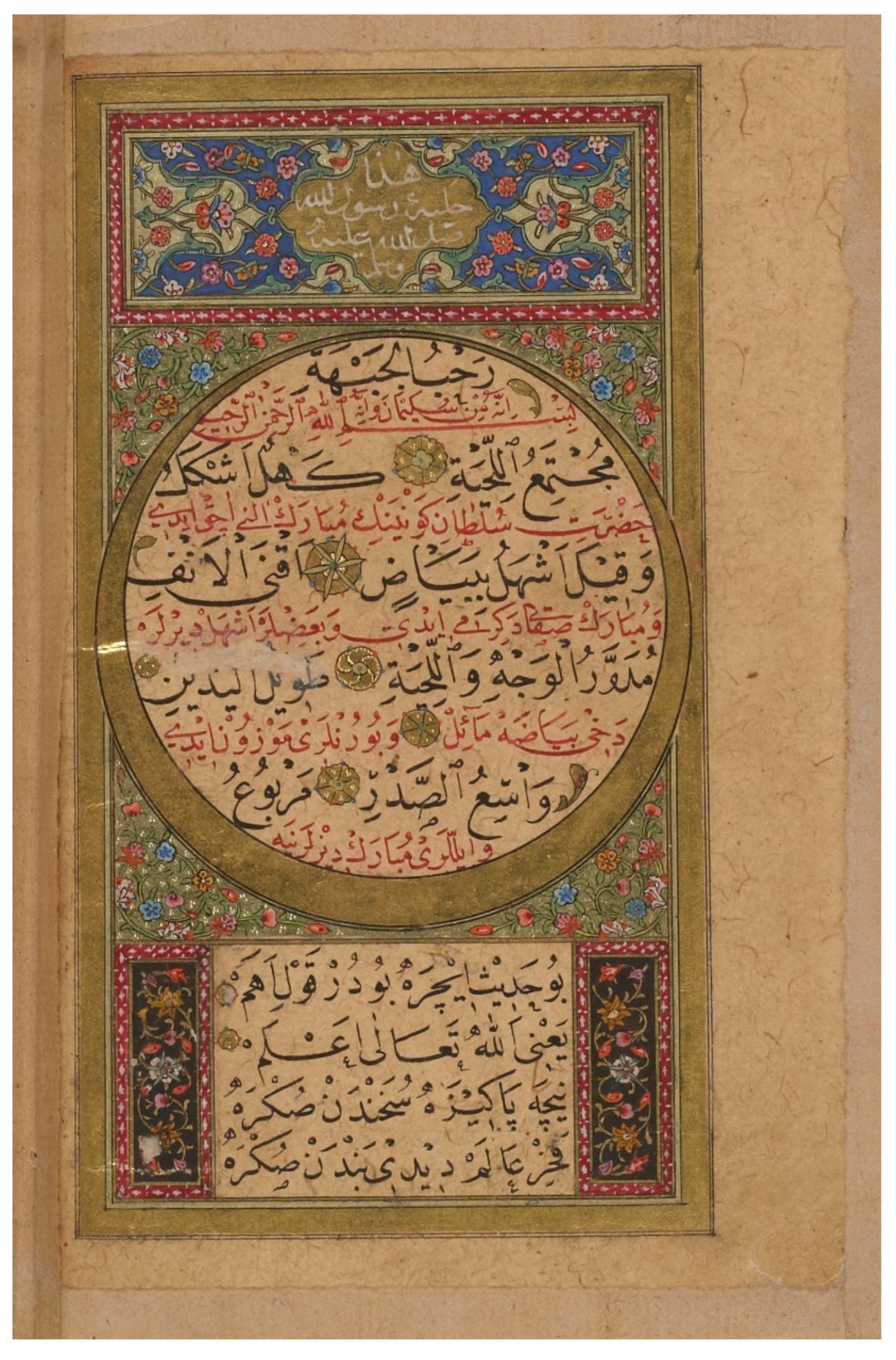

If these polemical debates are very much in the background of al-Kūmuljinawī’s arguments, equally important is the devotional atmosphere of early modern Islam, in which personal devotion and spiritual union with the person of Muḥammad had come to play a very important role indeed. There are many, many facets to this ‘devotional turn,’ but one of the most crucial was the desire to be ‘united’ to Muḥammad in some tangible sense, a desire that was facilitated by various devotional ‘technologies’ and interventions, in particular works of taṣliya (prayers and blessings upon the Prophet, though we are dealing here with a complex of terms and practices that are very difficult to render well in translation) such as the Dalā’il al-khayrāt, a work that hailed from late medieval Morocco but which by the end of the seventeenth century was effectively global. The desire for personal union (which, by the by, has strong late medieval and early modern analogues in other religious traditions- a topic that awaits serious investigation I believe) included a desire for and techniques towards visualization. Now, methods of spiritual visualization were not precisely new in early modern Islam, and they also existed for forging connections with one’s saintly master in a sufi ṭarīqa, but the devotional turn saw the proliferation of visualization, and its opening up to the generality of Muslims. Al-Kūmuljinawī and his cited authorities provide various routes for visualization, all of which might lead up to the actual literal seeing of Muḥammad’s physical form, as opposed to imaginal or spiritual visualization; there were other possibilities as well, most notably in the Ottoman context the popular ḥilye-i şerīf, a ‘textual icon,’ such as the one pictured below (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Arabe 6859 i., folio 5v.) and associated texts and textual images that sought to reproduce the Prophet’s image through imaginal and iconic means.

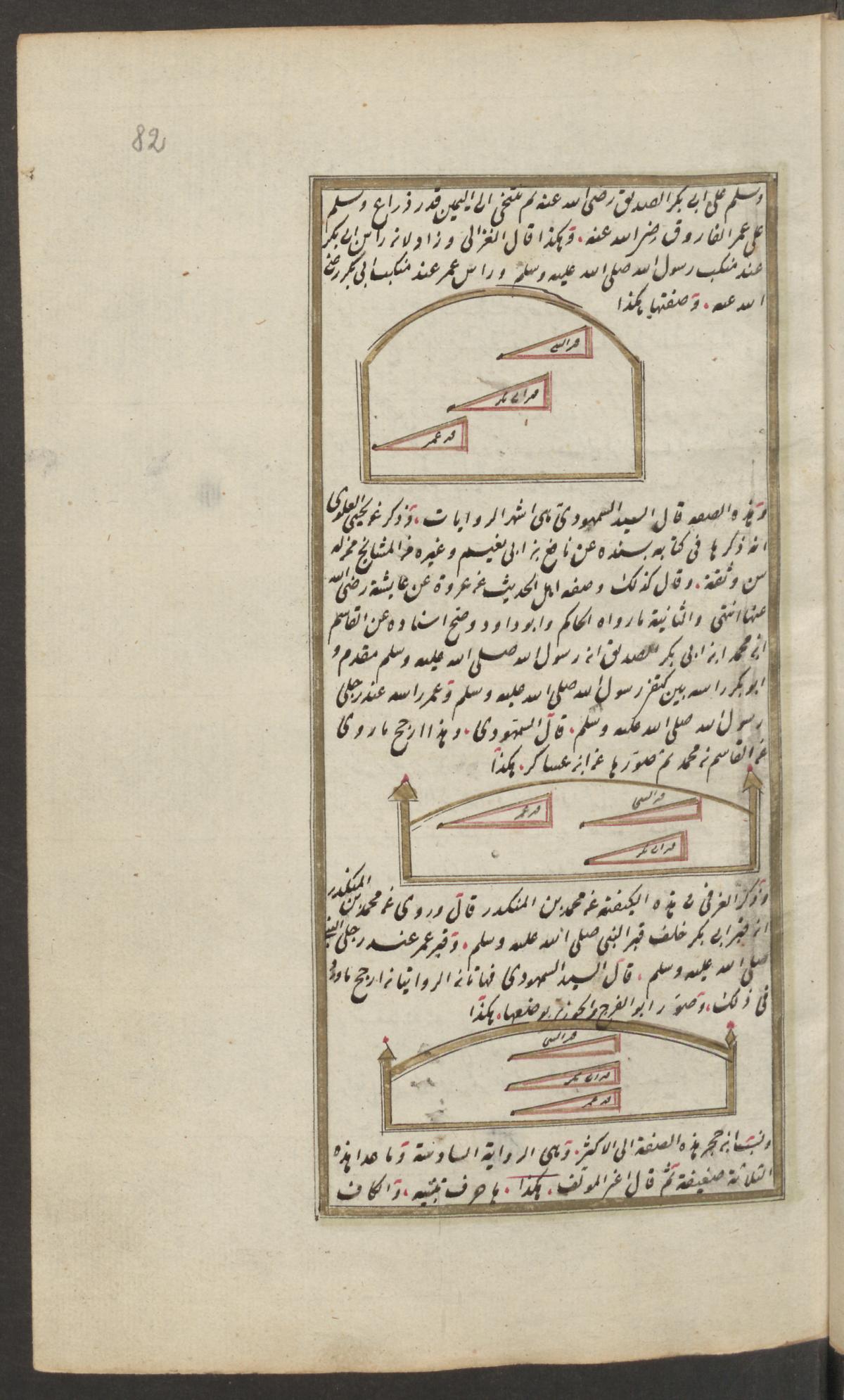

That then is the basic context of al-Kūmuljinawī’s arguments; we will return to them in the conclusion of this series and further parse his positions and objects. What I want to consider lastly here is his use of authorities: who are they, where did he come about them, and what can they tell us about book culture, epistemic communities, and the like? First, it’s notable, but not surprising, that the first bevy of authorities cited are all commentators: authors who took a primary, already canonical text (which could be quite old or relatively recent), and wrote a sharḥ, a commentary, on it. This was one of if not the primary modes of intellectual production in the late medieval and early modern Islamicate, so it is little surprise to see such authors dominating here. It is striking that al-Kūmuljinawī felt the need to indicate who two of the authors- al-Ajhūrī and Ibn Abī Jamra- were in the footnotes, which suggests they were somewhat less known than the next author he cites, Muḥammad Mahdī al-Fāsī (and indeed while I was familiar with al-Fāsī I had to look up the other two!). The author cited in the marginal note (al-Pāpardī or al-Pāpirdī) is one with whom I am not familiar, and could not locate, though he was probably a contemporary of our author and clearly Ottoman as well based on his name. Al-Fāsī is clearly an important source for al-Kūmuljinawī, which is not surprising: while he lived and worked in the Far West, this seventeenth century author would become very well known across the Ottoman world for his commentary on the Dalā’il al-khayrāt, copies of which (such as the one from which the image below hails, SBzB Hs. or. 5214) would have been fairly accessible for an author like al-Kūmuljinawī (for more on al-Fāsī, see Guy Burak, ‘Collating The Signs of Benevolent Deeds: Muḥammad Mahdī al-Fāsī’s Commentary on Muḥammad al-Jazūlī’s Dalā’il al-Khayrāt and Its Ottoman Readers’).

Interestingly, al-Ghazālī- probably the figure here best known to modern audiences- receives only a brief citation, and it is quite possible that al-Kūmuljinawī accessed the line in question via an anthology-type text or found it cited elsewhere. It is also striking that al-Kūmuljinawī procures his anecdote about the archetypal sufi ‘Abd al-Qādir al-Jilānī (or Gilānī, as here) from a compilation of saints’ lives, not from one of the ‘stand-alone’ hagiographies of the saint, which I suspect did not circulate as widely in the Turcophone part of the empire as in the Arabophone. The story related here is one that appears elsewhere, establishing the exalted status of this globally recognized saint; as I’ve noted elsewhere, it would be a fine idea for someone, or a team of someones, to buckle down and produce a history of devotion to al-Jilānī, as he really is everywhere in the late medieval to early modern (and modern!) Islamicate world. While probably not hailing from the oldest strata of hagiography devoted to al-Jilānī, the story is indeed pretty old, requiring explication for an obscure bit of vocabulary, our author drawing upon the most famous of Arabic dictionaries, the al-Qāmūs al-muḥīṭ of Fīrūzābādī. Not noted, perhaps because many readers would have picked up on it from familiarity, is that the sermon the saint delivers after the transfer of holy saliva (a whole other topic in its own right!) comes from a collection of such works, the Futūḥ al-ghayb, widely attributed to al-Jilānī historically (though probably in fact authored some years after his lifetime).

Alright, that’s probably enough for now- we’ll return to many of these themes in the final installment of this series, which will bring us to the end of this little work. I’d like to do more of these short series of ‘mini-editions’- if there is a particular genre or text in which you’re interested, feel free to let me know via comments or Twitter, and I’ll see if I can’t add it to the queue!

___________________________

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.