We have now met Shaykh Ṣafī al-Dīn (1252/3–1334), the eponym of the Safavid dynasty and one of the most important Muslim saints of the late medieval and early modern Persianate world, a few times, first as a young man seeking out the presence of other holy people, and then as an increasingly proficient adept in the arts of taṣawwuf. The extended story that I’ve translated and presented below (sans, I must confess, the Persian and Arabic couplets interspersed, which, time and energy pending I will later add) is set at a critical moment in the shaykh’s career, not long after the death of his primary shaykh, Shaykh Zāhid. While our source, the sprawling hagiographic treatment of Ibn Bazzāz (d. 1391–92), is somewhat circumspect around the details, it is clear that succession to Shaykh Zāhid’s post was contested. While Ṣafī al-Dīn laid claim to the succession, and was acclaimed by some of the late master’s followers, all was not well. The new shaykh was soon met with opposition, a group of ‘obstinate ones,’ in the words of the hagiography, forming and deciding to get rid of Shaykh Ṣafī al-Dīn, quite literally in fact, by killing him. In the rather (unintentionally?) humorous story that follows, while on his annual pilgrimage to the shrine of his departed master in Lāhijān near the coast of the Caspian Sea, this group, led by rival claimant to Shaykh Zāhid’s position Shaykhzāda Jamāl al-Dīn, the son of the late shaykh (hence his name, ‘shaykh-descendant’) and therefore seemingly possessed of a stronger claim. Not to give things away, but he does not win out, instead admitting defeat and being reconciled to Shaykh Ṣafī al-Dīn, who is shown being remarkably chill about the whole affair.

The story is relatively self-explanatory; worthy of note are various small but insightful details such as the presence of a female supporter of Ṣafī al-Dīn and her role in the tale, or the fact that some people at least in this world knew how to swim, whether for utilitarian purposes or for fun is not evident here.

It was Shaykh Ṣafī al-Dīn’s custom that at an appointed time he would go and make pious visitation (ziyārat u mazār) to Shaykh Zāhid’s tomb [in Lāhijān]. When that time came and he set out to make his pious visitation, Khwāja Fakhr al-Dīn Yusūf, who was the brother of the shaykh, came to the holy shaykh and said, ‘It is assuredly not safe for you to go and make pious visitation to Shaykh Zāhid, for a group of deficient obstinate ones are waiting in ambush, God forbid, to commit a sin!’

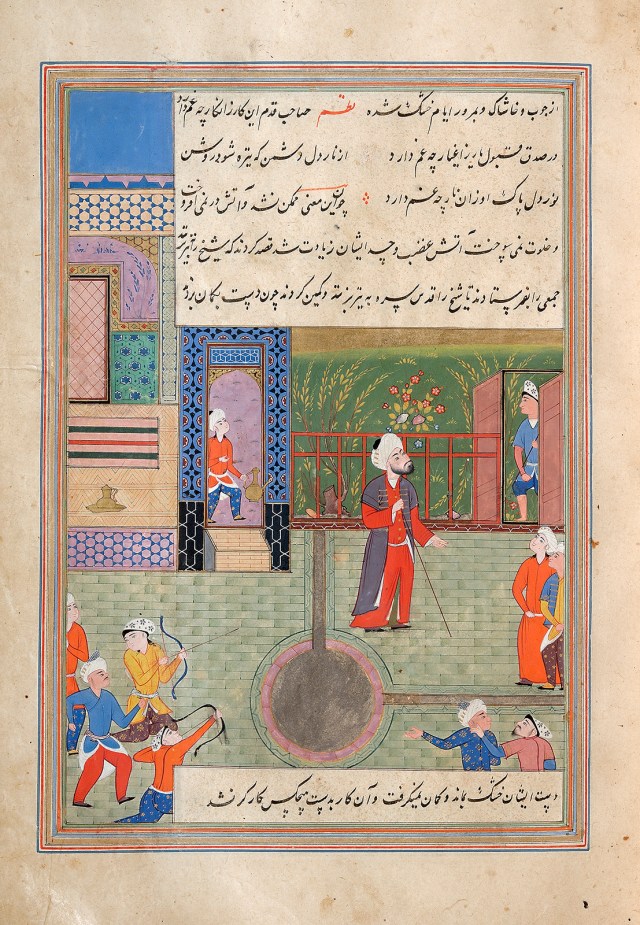

The shaykh, God sanctify his secret, replied: ‘If it is destined for me that in this time that in going I fall into their hands, then turning back the decree of God cannot be done, and if not, then there is no fear to be had.’ So the shaykh went on his pious visitation [as usual]. Through that group of obstinate ones the fire of obstinacy and anger was lit in Shaykhzāda Jamāl al-Dīn, God be merciful to him. They agreed to seek the death of the shaykh, God sanctify his secret, and furthermore agreed upon the means of killing him: they would set the shaykh’s retreat cell (khalwat) on fire, consuming the shaykh in the flames and so killing him. They came by night and first on the outside they fastened the door of the retreat cell shut with a nail so that when the fire blazed up [the shaykh] would be unable to come out. But when they lit the fire, due to the shaykh’s sainthood (vilāyat) the fire would not flame up and instead went out, even though houses and retreat cells in that place are all built of wood and beams which after a passage of time become dried out.

When this tack did not work, the flame not flaring up and the retreat cell not catching fire, the flame of their anger and envy only increased. They decided to shoot the shaykh with arrows. They sent out a party to shoot the shaykh from ambush. But when they put their hands to their bows, their hands were all dried out and unable to work the bows, none of their hands being able to work.

When their corrupt intention could not be realized by these sorts of stratagems, again they concluded that they would destroy the shaykh by using poison. So they put a measure of poison in honey and along with a sufra of food brought it before the shaykh, God sanctify his secret. However, the wife (ḥaram) of Shaykhzāda Jamāl al-Dīn, God be merciful to him, who was the mother of the departed Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad, God be merciful to him, secretly sent a message to the shaykh, God sanctify his secret, saying, ‘Take care! Do not stretch out your hand for the honey, beware against accepting any of it!’ When this condition was made known to the shaykh he was wary of the honey and did not accept any of it. And it was likewise with any food with which they schemed and plotted—that pious matron secretly gave report and the shaykh did not stretch out his hand to it.

When their vain desire and wish was not realized through this stratagem, they again determined that there was no other possible plan remaining save that at the time of [the shaykh’s] return [from the shrine of Shaykh Zāhid in Lāhijān], they would seat the shaykh in a boat, and a group of people who knew how to swim would also board the boat with him. Once they were underway in the water, they would sink the boat and escape by swimming, while the shaykh, God sanctify his secret, not knowing how to swim, would certainly sink with the boat and so die. In preparation for this task they donned light clothing, and wanted to board the ship and seat the shaykh in it. But, the shaykh said, ‘I saw Shaykh Zāhid, God sanctify his secret, coming towards me upon a gazelle-like horse and saying, “O Ṣafī! Ride upon this horse and travel the dry road—do not board the boat!”’

Having seen and heard this from Shaykh Zāhid, the shaykh, God sanctify his secret, said ‘I’m not going to travel by way of the water and will not be boarding the boat, rather, I’ll be going by dry land.’ This having happend, Shaykhzāda Jamāl al-Dīn saw that their idea [of getting rid of the shaykh] was never going to be feasible, so he went with the shaykh and spent an hour with him in his retreat cell. The shaykh, God sanctify his secret, said, ‘Shaykhzāda! I know what you aimed to do to me and what treachery against me became lodged in your heart—but God, exalted is He, has made it impossible for your goal to be achieved, even after this goal was repeated and enmity established. Yet, if your desire is for my destruction and cannot be otherwise, bring a measure of poison so that I can consume it and your intention be fulfilled, and no one else will be aware of this secret.’

When Shaykhzāda Jamāl al-Dīn heard these words, the sweat of shame ran down his face, and he sought forgiveness for this crime and begged clemency for his treachery. Having manifest purity of state, he brought forth the gazelle-like horse for the shaykh, and mounting him the shaykh made his return journey.

Ibn Bazzāz Ardabīlī, Ṣafvat al-ṣafā: dar tarjumah-ʼi aḥvāl va aqvāl va karāmāt-i Shaykh Ṣafī al-Dīn Isḥaq Ardabīlī, ed. Ghulām Riẓā Ṭabāṭabāʼī Majd (Tabriz: G.R. Ṭabāṭabāʼī Majd , 1373 [1994]), 798-791. Translated by Jonathan Parkes Allen, 2020.

If you would like to help keep the work I’m doing here going, do think about supporting me on a regular basis via Patreon. Thanks!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.