his oratory the high wide lands, stone and thin soil in

the broad neolithic scape, scrubbed and sky dried.

the heavens were closer there, thinner air, a world’s distance

from the city-god drenched plain hard by

the corrupting sea, the malarial reaches of power.

in hand his shepherd’s crook, passed down

from one hand to another a thousand generations,

memory accumulating like the mounded tepes,

lately transformed into a cruciform shape.

so he spoke to his God,

reading the words of the holy Book in the land,

his flock spread out before him—wisdom! let us attend.

he wept that he could not be

more akin to the creatures under his care,

heart burning with the great merciful weight of things.

closing his eyes under the sheltering tree,

Sozon the friend of God looked

inward, was shown what would come to be:

a martyr’s death awful to the telling, and

a holy spring welling up at his feet, for the ages,

watering the earth with his blood and with water.

his spirit spread into the dolomitic cracks,

up surged the water cold, mixed with blessing.

dream and the mothering earth’s pure drink,

portal and vision and life,

the Cross tossed in the charging waters.

he picked up his shepherd’s crook and set out.

down from his hard and rough untilled garden,

leaving his sheep in the care of another,

down to the city and its viscous charms,

exquisite violence and offal piles.

up against the vain rage

he came, and with his staff struck down

the graven gold in the thronging temple,

burst it into a thousand pieces,

a fine loot and bold, gathered up,

and gave it to the city’s poor. the roman concreted

places rang out with the challenge, and the answer

was iron against flesh, the singe of the sword, and then

death upon a tree.

still blood lusting and even more so full of fear,

they dragged his holy flesh out to the edge of the city,

lit a fire, in unknowing sign of the cataclysm to come,

but the sky mocked them, the elements

overpowered the small weak weaponed men,

storm washed over them and washed out their flame.

time and distance condensed in him,

the heavens stayed their small fires, a greater flame

burned still in his several parts, hot and holy.

water, and blood, and the venerable body marked

with the pain and the dislocation, set to earth,

and still he shepherds us, drawn from the old soil,

cut from the new cloth of salvation, old wine

mingled with the new. Blessed Sozon,

pray God for us, send us out from the unabiding city,

and lay your staff against the idols yet.

the wild old lands wait a returning.

Category: Orthodoxy

(lenten) thinking out loud, i: Scripture and the Resurrection in light of the deep history of life on earth

Alongside occasional posts outlining, in quite ‘uncooked’ and sporadic form, some of the current directions of my thought in relation to things like the history of technology and technics (particularly in relationship to the Islamicate world and our relationship to objects and bodies of historical inheritance therefrom in the present), at least during Lent this year I’d like to offer up some reflections, also quite sporadic and rapidly sketched, on theological and other issues that have been occupying my thinking lately, particular in relation to the deep evolutionary history of life on earth and its implications for Orthodox Christian theology and practice (I also have in the works a long essay on my own personal journey and perspectives on the controversy apprehension- or rejection!- of such a deep time perspective has occasioned in Christianity). The following is then an initial exploration, precipitated by a passage by St. Gregory of Nyssa, of the intersect of Scriptural views of the created order, the deep evolutionary history of life on earth as expressed in our genetic ‘archive,’ and the Incarnation, Death, and Resurrection of Christ.

Our takeaway from Patristic explorations of science and theology should not be to adopt their particular interpretations, in the majority of cases anyway, given that while impressive for the era, and in a genealogical line forward to much our own body of epistemic workings out, the majority of that scientific knowledge is now entirely antiquated if not downright quaint. What counts is the same thing that counts about the production of that knowledge in the first place, as well as the theological routes visible in the Scriptures: not the particulars but the processes and the underlying presuppositions about the order and legibility of the universe and its relationship to God. St. Gregory is entirely comfortable thinking about divine creation in terms of the prevailing science—we might rather say natural philosophy—not to make Scripture say something novel but rather to read Scripture in light of what was then known about the natural world (and in this regard we can in fact see multiple strategies from the Fathers, precisely as we would expect for anyone with a genuinely high view of Scripture and its inspiration—that it can sustain many meanings and interpretative paths across chronological spans). In St. Gregory’s case the basic message that he—rightly I think—sees in the Genesis account as having to do with the place of humans in the created order and in relation to God is pretty readily transposable to what we know of evolutionary history. There is, as Genesis in fact suggests pretty overtly, continuity—we would say genetic continuity—between ourselves and all previous lifeforms, and we carry the evolutionary traces of them in ourselves, in our sensations and our instincts. And as part of God’s good creation, this evolutionary inheritance is fundamentally good, it is a part of the biological package necessary for life. Sin results in our misuse of our evolutionary heritage, and we alone of all creatures can make use, or misuse, of our biological inheritance precisely because we possess consciousness (in St. Gregory’s parlance, ‘reason’) and a soul, which I think we really ought to think of as shorthand for our unique relationship with God—the other principle lesson of the Genesis account. That consciousness and that relationship with God, of course, entail our free will, our being moral creatures who can ascend towards God and divine transformation or who can descend towards sin and destruction (of ourselves and of the wider creation, which ‘groans’ in anticipation of its transformation through God working in and with us).

Of course none of this per se speaks to whether we ought to understand Adam and Eve as pointing towards literal discrete historical figures or something else: I really do not think the story itself indicates one way or the other all that conclusively, and can be read in multiple ways, indeed, demands multiple readings and interpretive routes by, among other things, the inclusion of not one but two origins stories for Adam and Eve right there in the opening chapters of Genesis. The details and perhaps the relationship to historical time are different in each, but the basic gist is the same: humans are creatures derived from the same origins as all other creatures, ultimately the fruit of the earth itself, but who are given a special relationship with God and carry His image, and are instructed by God to live in a particular relationship with Him and the created order, but are capable of contravening that relationship, with their sin ultimately having ‘real-world’ effects within the wider creation and within human self and society. God calls us bipedal, consciousness-bearing hominids to a special status in the world, to inhabit the created order as creatures ourselves in kinship with all other living things but as points of contact with God, as priests and worshipers who are in the world yet consciously (and freely!) oriented towards God. That of course is half of the story: the second half (though really it is the entire story) is that God Himself enters into the stream of evolutionary time and development, a stream that we as humans were meant to transfigure and transform, not from a bad state to a good state but to a transformed state, one only realized through in a sense deiform created beings simultaneously in relation to the wider natural world of which they are a part and in relation to God and the suprasensual order of the spiritual world and of Divine Life Itself.

St. Gregory would have been very excited to learn, I think, that humans quite literally carry within their genetic code a record of their deep past reaching back to the earliest life forms (even if the signal thereof is no longer visible to us down to the earliest periods), we contain within ourselves a continuous and cohesive expression of the wider living created order in a quite concrete sense—and that in becoming human God the Son took on in a manner beyond comprehension the whole history of life as contained and expressed in our humanity, in the genetic code that generates our biological reality. In rising to life again Christ quite literally brings to life, brings to divine life and being and transformation—transfiguration—not just humans as discrete entities but humans as bearers of the whole previous history of life on earth (that is, one such trajectory, standing in as it were for the many others), assembled from the fundamental elements of the earth—and so bears into divine life all of creation as expressed in our genetic history and physical-chemical assembly, a genetic history that contains a record of specifically human history, too, including our sin and acts against divine order. At a cultural level, it is no accident that Christ was incarnate in a particular time and place speaking a particular language within a particular cultural sphere. For much as our genetic code and its epigenetic expression doesn’t just relate but really is the cumulative expression of creation’s whole past and present, culture—particularly language—is itself the record and the expression of the deep human past, of its good and bad and terrible. Christ literally physically bore in Himself, in the humanity He received from the Theotokos, the whole sweep of the evolutionary history of life, the cosmological history of matter, and the cultural history of human society—and in dying and rising again He completed the arc of transformation invested in us and, in a sense, fulfilled by us in the person of Christ, who is not just the ‘second Adam’—that is, human—but is indeed the ‘true Adam,’ the true human. Christ models in Himself and specifically in His post-Resurrection interactions with His disciples the ultimate end of the created order, the full trajectory of the history of the cosmos and of life on earth: not replacement or effacement or even radical rupture but transformation, a form of being at once very much continuous with and yet in other ways inconceivable in relation to current life. Scripture gives us really no ‘hard details’ about the ‘after,’ just as we cannot extract a theory of evolution or cosmological expansion or really any such details from the creation accounts of Scripture. We are given indications and clues in Scripture, outlines and stories; for the large arc of life’s history scientific inquiry can fill in many gaps, if not explain things theologically really. For the future of the created order’s trajectory, for what the salvation and transformation in Christ looks like, again, we have hints and clues, stories and symbols—and, as a sort of prefigurative ‘fossil’ record if you like, the life of the Church and the lives of the saints, men and women who embody to a visible extent the life of Christ in the here-and-now, before- in a strict chronological sense at least- the general Resurrection, yet also within and through that Resurrection.

Vardapet Poghōs and the Goats

Vardapet Poghōs, the protagonist of the following little story, taken from the mid-17th century Armenian chronicle (which also contains ample hagiography of contemporary saints) of Aṛakʻel of Tabriz, has been featured in these pages before. This charming account follows in a similar vein to the one linked to above: Due to his attempts at reforming aspects of Armenian church life that he saw as corrupted, Vardepet Poghōs had fallen afoul of an ecclesial foe who had tried to have him prosecuted by the Safavid governor of Erevan. However, the local khan was impressed with the saintly vardapet and rejected the charges against him, instead allowing him to return home, even dispatching a soldier to travel with him. While not stated explicitly, it is implied and we can safely assume that the soldier was a Muslim, though instead of being a cause of antagonism this confessional difference becomes a means for the Christian saint to demonstrate his sanctity.

The vardapet and the soldier left Erevan and traveled to the gawaṛ of Goght’n. They reached the village of Shoṛot’, left it and went toward the village of Ts’ghna. They went on the road that goes along the river that flows from Norakert to Beghewi. But, before they reached the river, they saw that wild goats were eating grass on the plain. There were twelve of them. The vardapet called and the goats came to him. The soldier was not aware that the vardapet had called them, for he was farther away from the vardapet. Seeing that the goats had stopped, he immediately took up his bow to strike them with his arrow. The goats were frightened and immediately took off from where they were standing and began to run away toward the mountains. The vardapet glanced and saw that the soldier was responsible for this. He reproached him and forced him to lower his bow. He then again called the goats, saying, ‘Come with the blessing of God; come to me, I shall not let anyone harm you.’ Behaving like people, with reason, they came to the vardapet once more and stood before him. The vardapet approached them and stroked them with his hand, scratched their necks and backs, hugged them gently and talked to them as with intelligent beasts. The goats stood before him for a long time. The vardapet then said to them, “Go in peace to your pasture. May God guard you as you wish.” They then went on their way to the mountain. The soldier stood by astounded and amazed by all this. The saintly vardapet began to tell him about the miracles performed by the saintly apostle Thaddeus, who brought wild deer to Voski and his comrades.

Aṛakʻel of Tabriz, The history of Vardapet Aṛakʻel of Tabriz ( Patmutʻiwn Aṛakʻel Vardapeti Dawrizhetsʻwoy) Translated by George A Bournoutian. (Costa Mesa, Calif.: Mazda Publishers, 2005), 206-207.

Shared Ottoman Worlds of Imagination

The two images in this post come from almost contemporary Ottoman manuscripts, one (above), a major work of history in Ottoman Turkish, the Zubdat al-tawârîḫ of Sayyid Lokmân produced in Istanbul, the other (below) a sort of abridged Bible (though it might be better thought of as an exegetical textual and visual condensation and rearrangement of the Bible) in Armenian, produced in Amida (modern-day Diyarbakır). The Zubdat was completed in 1590, while the Bible chart- and chart is probably the aptest term here- in 1601. There is much that could be said about these texts, and the Zubdat has been studied both for its art historical value as well as in reference to recent scholarly literature on Ottoman historiography and memory construction. The Armenian text (though neither work is fully described by ‘text’ in any meaningful sense) may have been studied in some context but I myself am not aware of any such work.

What struck me in looking at these two manuscripts side-by-side, as it were, is the similarity in the visual structuring of the information on the page. Both manuscripts employ a similar cartographic, architectural style, even if the details and other artistic traditions at work obviously vary. In the one history in a universal (but still very much ‘sacred’) key is displayed and ‘mapped,’ in the other history as a part of the Biblical narrative. Images of important figures are framed- literally- by architectural details, while names and terms are mapped out along the page in hierarchical, linked order, the little textual roundels like points on a map.

No doubt there is much that could be made of the similarities in these works, similarities which suggest shared ways of organizing and visualizing information, the relationship of text and space, as well as understandings of the nature of scripture and history. Determining why these similarities exist would require examining just such shared contexts as well as other historical, and perhaps Ottoman-specific, developments and historical rhythms. These two works placed in dialogue are also a good demonstration of the limitations of ‘influence’ as a category of analysis: completed within ten years of one another, one in the world of the Topkapı at the imperial, the other in an Armenian scriptorium at the eastern edge of the empire, the came into being all but simultaneously, and point to contexts and historical currents operative across the empire and through multiple social and cultural channels, not confined to particular locations or to one religious and linguistic tradition only.

Print Culture Remixed: Safavid Painting Across Confessional Boundaries

The four images in this post- two from Western Europe, two from the Safavid Empire- paint a picture of the inter-connectivity of places, religious communities, and cultural traditions of early modern western Eurasia, inter-connectivity that took place without any single power or region dominating, as would be true from the nineteenth century forward. These images also illustrate the problems with the language of ‘influence,’ as well as the fact that religious communities and traditions that were at odds in some respects could still participate in shared cultural paradigms and draw upon the work and concepts of others in creative ways. In particular these images demonstrate the complicated place of ‘print culture’ in a Eurasian context, printed texts co-existing and interacting with non-print modes well through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

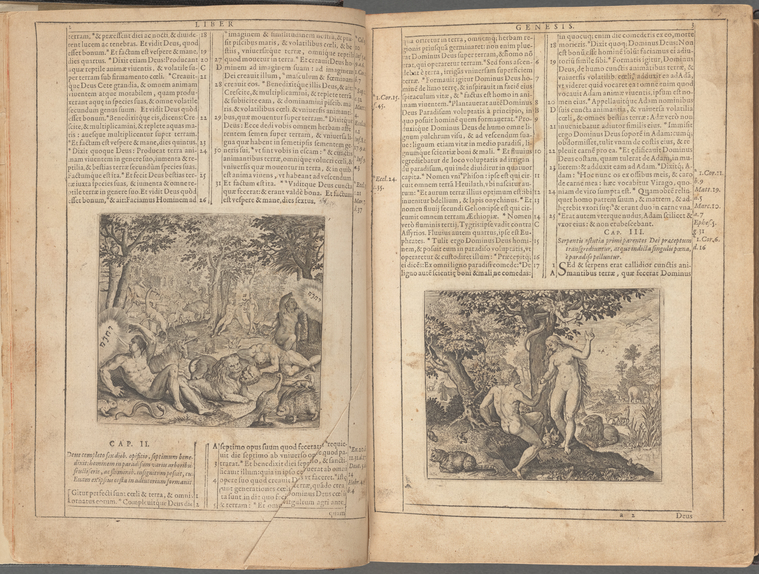

In this first pair of images, Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, illustrating the first chapters of Genesis, the Armenian illustrator Hayrapet Jul’ayec’i has drawn upon the images of Johann Theodor de Bry for his own illumination of the Bible. The relationship is obvious upon even casual examination, such that one might be tempted to call the Armenian paintings ‘copies.’ But slightly closer examination reveals something more subtle going on. Jul’ayec’i has followed the general form and many of the details of de Bry’s engravings, but has done so in a transformative way: the images have been placed in a new arrangement, one that proceeds in chronological order from left to right, the borders dividing the scenes employing motifs with deep roots in Armenian illumination. Most significantly, Jul’ayec’i has rendered these scenes in color, in brilliant color which calls to mind earlier illumined Armenian Bibles. The entire production has furthermore been placed within a manuscript Bible, instead of the printed Bible of de Bry. The reference to de Bry, and by extension, Western European art conventions, remains unmistakable- but in rendering them in the bright splashes of Armenian painting they have been translated and re-appropriated (there is literal translation as well- note the inclusion of Armenian text in Jul’ayec’i’s painting). ‘Remix’ is one way of thinking about such a piece, the form remaining but the interpretation rendered making the piece an effectively new creation, the mood and resonances it conveys departing dramatically from the original ‘cited’ imagery, even as the new art depends on the original to some degree.

What is particularly notable about Jul’ayec’i’s art, and that of the many other Armenian artists and manuscript producers who employed similar techniques vis-a-vis print culture circulating in Armenian communities (which in itself reminds us that it was not unusual for a Bible printed in the Netherlands to end up in the Safavid lands), is that Armenians were not themselves strangers to print culture. The first Armenian book was printed in 1512, with an increasing pace of printing in a number of presses across the vast Armenian world of western Eurasia. Simultaneously, Armenians produced, sponsored, and purchased manuscripts such as that from which contain Jul’ayec’i’s illuminations. Print culture was useful for some things, while manuscript culture and its associated arts continued to play an important role, from liturgical texts to diaries to magical scrolls. And just as manuscript arts and traditions left their imprint in Armenian print culture (and many other iterations of print culture across early modern Eurasia), the new possibilities that printing opened up could find their way into manuscript production.

In the Safavid world, Armenians were not the only people creatively adapting and ‘remixing’ Western European print culture material. Persian-speaking Muslim artists, such as the seventeenth century painter Muhammad Zaman, were also making interesting use of imagery circulating out of Western Europe. Witness Zaman’s rendering of the iconic scene of Judith with the head of Holofernes:

Isfahan, Safavid Iran (Khalili Collections MSS 1005).

Zaman’s depiction of this scene incorporates material from an etching of a painting by the fifteenth century Italian artist Andrea Mantegna (fig. 4). But just as his Armenian contemporary had done with de Bry’s etchings, Zaman has transformed the scene. It is now in bright and vivid color, reminiscent of more traditional forms of Persianate miniature (which itself had long been in dialogue with Armenian painting). Just as Jul’ayec’i reframed his source material, Zaman has not only filled out the scene around Judith and her maidservant with lush vegetation, vivid flora, and a scene of a camp and a city in the background, but in keeping with the conventions of Persianate art he has embedded his painting within a series of frames, frames that are as much a part of the painting as the main image itself. Particularly strikingly, he has filled the upper panel with realistic flowers, flora typical of alpine Eurasia such as primroses and irises. The result is a striking contrast between the delicate beauty of the flowers and the gory sight of Holofernes’ head being held aloft, a somewhat incongruous scene. What would Zaman’s viewers have taken away from this painting? Would they have known to what it was referring, whether in terms of story or in terms of the source in Andrea Mantegna’s depiction? The Western European elements, as in the Armenian imagery above, are unmistakable, diverging as they do from the canons of Persianate art: yet they have been rendered into a Persianate style and frame (literally and figuratively). Some of the meaning is retained, while other aspects are transformed- for instance, it is possible that most viewers would not have known the story itself, leading them to imagine their own story or to connect the image with stories they did know. Continue reading “Print Culture Remixed: Safavid Painting Across Confessional Boundaries”

A Tale of Two Holy Wells in Early Modern Constantinople

Just outside the Theodosian Walls of Istanbul is a spring which is today accessible from beneath a church of nineteenth century vintage, reached by a flight of marble stairs down into the living stone, a spring known as Zoödochos Pege (the ‘Life Giving Spring’) in Greek, Balıklı Ayazması (the ‘Fish Spring’) in Turkish, both names alluding to important features of this site of pilgrimage. One of numerous ayazmas, or holy wells, that appeared in and around Byzantine Constantinople and many of which have survived as places of veneration in modern Istanbul, the Zoödochos Pege is one of the most storied and most visited, from late antiquity to the present (it’s one of the handful of ayazmas I’ve visited, in fact). Long associated with the presence and activity of the Theotokos- as can be immediately surmised from the icon above- the spring’s veneration probably began during the reign of Justinian (527-565), though it might have begun even earlier, a vast trove of miracle accounts associated with the healing powers of the spring, blessed by the Theotokos, accumulating over the centuries. By Ottoman times, which are my concern here, the church above the spring had fallen into ruin, perhaps even before Mehmed II’s conquest of the city. Until the 1720s pilgrims visited a holy well that was, at least in part, out in the open, much as the icons I’ve selected here indicate (though they suggest a location on the surface of the ground, not essentially underground as was almost certainly true then and is definitely the case now.

The early modern Ottoman period seems to have seen a surge in interest in and veneration of this holy well, if we are to go by the numerous iconographic depictions that began to appear in the seventeenth, quite a few of which made their way into the Wellcome Collection (by a route unknown to me), from which I have drawn the two examples featured here. The above icon (fig. 1) lays out several repeating elements in these depictions, depictions which probably brought together a range of traditions and stories circulating among devotees: gathered around the stone basin of the holy well are representatives of miracle accounts, some whose stories we can easily put together- a man rising from his bed, a mother holding a healed child- others less evident to us now. The potency of the holy water of the well underlines each vignette, however, with the enthroned Theotokos and Christ rising above the waters, radiating holiness down into the well. The famed fish are also visible, themselves a part of the sacredness of the well, as the Turkish name indicates. This icon also features a row of ‘supporting figures’: St. John the Forerunner, Sts. Helena and Constantine at the Invention of the Cross, and a third saint, perhaps St. Mamas, an extremely popular saint during the Ottoman period. The icon is in rather rough shape, having been scratched or scraped at various points- not as iconoclastic damage (which would have targeted faces), but in order to use the scraped material for blessing, a way to participate in the holy power of the spring at a remove, as it were. The second icon I’ve included (fig. 2), at the end of this article, probably dates from the eighteenth century, and reproduces much of the same visual material as that above, but with the addition within the image of a stream of text coming from the Christ Child to a soldier, along with a gilded frame without. What drove this evident resurgence of interest in and devotion to the Zoödochos Pege? I am not sure, though, as I will hopefully soon discuss in a later post, early modern Ottoman Christians and Muslims alike expressed renewed devotions, often expressed visually, to their various holy places, from the seventeenth century forward. And indeed, it is possible, as the story of the second holy well might indicate, that it was not only only Orthodox Christians visiting this ayazma, but Muslims as well, which might help us understand the resurgence in interest of this particular ayazma, as a competitive process.

Less than a mile north of the Zoödochos Pege is the zaviye complex of a prominent Muslim saint of 16th century Constantinople, Merkez Efendi (d. 959/1552). While it does not seem to be very prominent today, this site also features a holy well, along with several other sites of veneration, at least in the early modern period, as described by Hafız Hüseyin Ayvansarayî in his late eighteenth century guide to the mosques and other religious structures in and around Istanbul: ‘There is an exalted ayazma in the vicinity of Şeyh Merkez Efendi’s tomb. One descends to it by steps. The abovementioned [Merkez Efendi’s] subterranean halvethane, which is like a cave, is still extant, and it is a place of pilgrimage for the Faithful [1]. The hamam located next to [Merkez Efendi’s zaviye] is one of its vakfs. The aforesaid [Merkez Efendi] had a private room in the hamam for bathing. At present the sick and invalid bathe [there] with purity of purpose and are restored to health.’ [2]

Continue reading “A Tale of Two Holy Wells in Early Modern Constantinople”

Saints and the Crossing of Confessional Boundaries in the Ottoman and Safavid Worlds: Part ii.

The modern history of relations between Muslims and the Armenian Orthodox of Anatolia, Azarbaijan, and other parts of the former Ottoman Empire has not been happy one for the most part, and in both popular memory and in historical scholarship pogroms, dislocation, erasure, and genocide have been foremost concerns, and for good reason given the ongoing discourses and actions of denial and erasure in the region. However, that focus has often resulted in lack of attention to the complexities of relationships between Armenians and their Muslim neighbors, relationships that historically were marked by more than just antagonism (though conflict did exist). The following story, which reflects a different iteration of the ‘shared economy of holiness’ that we explored in an earlier post, comes from Aṛak’el of Tabriz’s magisterial volume of history that deals with Armenians in the Safavid Empire and beyond during the 17th century, and which includes within it several sustained hagiographic accounts of contemporary- to Aṛak’el- Armenian saints, saints who sought to ‘reform’ and restructure Armenian Orthodoxy through preaching, educating and disciplining clergy and monastics, and building or renovating local church infrastructure. While, according to Aṛak’el’s accounts, these saintly vardapets (a vardapet is a type of monastic preacher and scholar in the Armenian Church) practiced intense personal holiness and strove for the good of the Armenian people and faith, they ran up against entrenched powers in the hierarchy, and as a result sometimes ran afoul of Safavid officials. Interestingly, however, many of the stories of conflict that Aṛak’el tells involve Armenian Christian instigators who go before Muslim Safavid officials and level charges against the saintly protagonists.

Such is the milieu in which this story takes place. Vardapet Poghōs, one of the key saints in Aṛak’el’s history, had incurred the wrath of a range of prominent church officials in his efforts to revive parish life in the far northwestern corner of the Safavid realm. The encounter described in the following account occurs while Poghōs and his disciples are on their way to visit Shah Abbās II in order to clear their name. The encounter between the Armenian saint and the pious Muslim householder that takes place in the midst of this journey is a good symbol of the ways in which holy men and women might be recognized across confessional boundaries, even as prominent people within their own community did not recognize their holiness, for various reasons. Şeyh Hasan Efendi, the subject of part one of this installment, was in a similar state, as he was opposed by Ottoman Muslims of a ‘puritanical’ bent, even as he was evidently recognized as holy by at least some of his Christian neighbors. At the everyday level, it seems, early modern people in the Islamicate world, of which Armenians were an integral part, sought to recognize the friends of God in whatever form or place they might be found, since such holy men and women might provide a crucial source of safety and aid in an often hostile and uncertain world. Holy men and women themselves- including those such as both Vardapet Poghōs and Şeyh Hasan who were clearly deeply committed to the creedal precepts and claims of their respective faiths- were more often than not in this period accepting of such ‘ecumenical’ encounters.

When they reached the gawaṛ called Araghbar at dusk, they entered a Muslim village to spend the night there. It so happened that they encountered a man, a Muslim, who came out to greet them. He implored them, saying, “I beg you, for God’s sake, do not abhor that I am a Muslim, but pay heed to my request and enter my house so that I may show you my hospitality. For I have made a vow to God not to eat anything today without a guest. I have been standing here in the middle of the village seeking a guest. God has sent you! I therefore, ask you to enter my house.” The blessed vardapet [Poghōs] answered the man happily and said, “Let it be as you wish. We shall go to your house.” They spent the night at that man’s house and he received them very well. He gave them everything they required for their rest. In the morning, before they prepared to leave, the Muslim man came and implored them, saying, “I have no son, and no one will remember me on this earth. I beg you to pray for me, so that I shall have a son, for my wife is barren.”

The saintly vardapet lifted his habitually outstretched hands to the sky and prayed adamantly to the Lord to give the man a son. The benevolent Lord, who had promised to give His followers whatever they requested in faith, granted the man a son because of the saintly vardapet’s prayers. The same man later informed us of this. For, after some time, the Muslim man came, thanked the vardapet during the Divine Liturgy, bowed down, thanked him, praised him, and said, “Because of your prayers, God has granted me a son. I now beg you to pray that God grant him a long life.” The saintly vardapet prayed for him again, comforted him for some time and then let him go.

Aṛakʻel of Tabriz, The history of Vardapet Aṛakʻel of Tabriz ( Patmutʻiwn Aṛakʻel Vardapeti Dawrizhetsʻwoy) Translated by George A Bournoutian. (Costa Mesa, Calif.: Mazda Publishers, 2005), 202-203.

Saints and the Crossing of Confessional Boundaries in the Ottoman and Safavid Worlds: Part i.

The two accounts that I’ve selected for this and an upcoming installment come from two milieus that at first glance might seem very different but upon a closer look reveal some striking similarities, similarities that reflect shared ways of seeing the world and ways of relating to people of different religious and confessional traditions, even in an early modern world marked by frequent conflicts and debates over confessional boundaries. The first story comes from an Ottoman Turkish source we’ve explored here previously, the menâkıb (saint’s life) of Hasan Ünsî, an eighteenth century Muslim saint of Istanbul, while the second installment, originally composed in grabar (‘classical’) Armenian, will be an excerpt from the life of Vardapet Poghōs, a seventeenth century Armenian Orthodox saint whose career took place in the northwest corner of the Safavid domains, in what is now Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iran.

Here is the account from Hasan Ünsî’s menâkıb, with my commentary following:

‘Near the door of the exalted tekke there lived a Christian doctor, named Mikel, who was skillful and wise in the knowledge of medicine. It was his custom that if a sick person came to him and his treatment was not effective or treatment was not even possible, he would say to the patient, “The cure for this illness is inside this tekke, so go to the tekke, and find the Şeyh therein. His name is Hasan Efendi—go to him, he can treat this illness. Its cure will come from the Şeyh, so that you’ll have no need of other than him.” So saying he would send the sick person to the venerable Şeyh. This Mikel was consistent in this practice.

‘One day this poor one [Ibrahim Hâs] had gathered along with the other dervishes before the candle-like beauty of the venerable Şeyh, deriving abundant benefit from the sight of the saint. We saw that two people had come within the door. One had nothing upon his head but a wrapped around piece of cloth. He came up to the venerable Şeyh, kissed his blessed hand, and sat down. The venerable Şeyh said to him, “Have you come from afar?” He replied, “We are from afar.” The man whose head was wrapped in a piece of cloth came before the Şeyh, lifted the piece of cloth from his head and showed his head to the venerable Şeyh. As he turned we all saw that his head was entirely in boils (çıbanlar). Each one was jagged like the shell of a hazelnut and very red, without numerous individuals boils—they were about thirty in number, but each boil was very bad—we take refuge in God! This person said, “My Sultan, thus with this sickness I have been tried. I cannot put anything on my head. I have sought someone to treat it in both Istanbul and Galata, but no physician understands this sickness, and they give no answer. Despite expending many akças I have neither cure nor respite. The physicians of this city are incapable of treating me! Finally, near this tekke’s door there is a physician to whom I came and showed the boils on my head, and he said to me that ‘We have no means of treating this illness. But the doctor for this illness is the şeyh of this tekke, who is named Hasan Efendi. The cure for this is there.’ Saying this he sent me to your side. Will you give me an electuary, or give me a pill? Or perhaps you will give me some other treatment—whatever you say, let it be upon my head! I remain without a cure!”

The venerable Şeyh smiled and said, “Mikel has given you a good report; but you did not quite understand if you seek from us an electuary or pill.” Having said this, he said to the man, “Come before me!” He came before him and uncovered his head. The venerable Şeyh said to him, “Bend your head towards me!” He bent his head, and the venerable Şeyh spit into his hands and placed them on the boils of the man’s head, and then for one time gently hit them. He then said, “This is our pill, electuary, and şerbet! Go now, and henceforward you will be well, whether you believe or don’t believe.’ The venerable Şeyh said no invocation, read no prayers, nor said the Fatiha over him. Then the man kissed the venerable Şeyh’s blessed hand and left. Two days later that person came to the venerable Şeyh and we saw that the boils had gone, he was well, and was wearing a quilted turban (kavuk). He had brought many gifts and much praise. Afterwards he came face-to-face with the venerable Şeyh with his gift, but the Şeyh strongly enjoined him not to tell anyone, but [the story] was circulated among the poor ones [the dervishes].

İbrahim Hâs, Hasan Ünsî Halvetî ve Menâkıbnâmesi, edited by Mustafâ Tatcı (Bağcılar, İstanbul: Kırkambar Kitaplığı, 2013, 2013), 314-317. Translated by Jonathan Parkes Allen, 2018.

What might we make of this story? It gets at, I think, an important feature of religious life in not just the Ottoman world but much of the rest of early modern Eurasia: the potential power of sanctity, as invested in a holy person, place, or object, had a decided ecumenical quality. There is no sense here that either Mikel of Hasan Ünsî were rejecting their confessional affiliations, or even questioning the validity of their respective faiths. But we do get the sense of a shared economy of sanctity among them, and among the unfortunate patient and the various onlookers. The story does not end, note, in anyone’s conversion (unlike any number of medieval Islamic saints’ lives), and Şeyh Hasan is explicitly described as not using overtly Islamic methods in treating the man (whom we are given to understand, I think, to be non-Muslim himself, though this is not made explicit). Mikel the Christian doctor does not become Muslim, either, and we get the sense that Şeyh Hasan quite appreciates the referrals he receives from him. The saint’s power has an open quality, at least towards ‘ordinary’ people- elsewhere the saint is shown restricting access to himself when he is sought out by more powerful and wealthier people with ties to the Ottoman ruling elite. Continue reading “Saints and the Crossing of Confessional Boundaries in the Ottoman and Safavid Worlds: Part i.”

Questions and Answers with the Elders of Gaza

Saints Barsanuphius and John (who was also known as John the Prophet) settled in the vicinity of Gaza, Palestine at some point during the reign of Justinian; the exact dates of their deaths are unknown though they are commemorated together in the Orthodox Church on February 6. Barsanuphius was of Coptic origin, having begun his monastic life in the fabled desert of Egypt, but, like many others in his time, he eventually traveled north into Palestine where he and his contemporaries developed a new form of embedded- quite literally in his case- monasticism in the well-populated countryside of Palestine. Barsanuphius and his disciple, John, who would come and settled alongside his master and live beside him for eighteen years, both practiced strict seclusion, communicating primarily through letters and intermediaries. However, their reputation drew other more conventional monsastics, and soon a thriving monastic community with handicraft production, medical services, a church, and other features grew up around them. Both Barsanuphius and John acted as spiritual counselors to not just the monastics around them but to ordinary laypeople in the nearby communities. Drawing upon years of spiritual practice and discernment, these two men provided careful and sympathetic, but frequently powerful and insightful, responses to the questions- some profound, some very quotidian- directed towards them. Below is a selection of these questions and answers, with an emphasis on matters pertaining to laypeople.

444. Question: If I am distracted during prayer, what should I do?

Response by Barsanuphius: If you are praying to God and become distracted, struggle until you begin to pray without distraction. And keep your intellect alert in order that it does not become too lofty. Nonetheless, should this occur, since we are weak, persist to the very end of your prayer; then prick your heart, and say with compunction, “Lord, have mercy on me and forgive me all of my offenses.” And, afterward, you will receive forgiveness of all your offenses as well as of the distraction that occurred at the beginning of your prayer.

463. A Christ-loving layperson asked the same Old Man [John] if one should reflect a great deal about the sacred mysteries, and whether a sinful person approaching these would be condemned as being unworthy.

Response by John: When you enter the holies, pay attention and have no doubt that you are about to receive the Body and Blood of Christ; indeed, this is the truth. As for how this is the case, do not reflect on it too much. According to him who said, “Take, eat; for this is my body and blood,” these were given to us for the forgiveness of our sins. One who believes this, we hope, will not be condemned.

Therefore, do not prevent yourself from approaching by judging yourself as being a sinner. Believe, rather, that a sinner who approaches the Savior is rendered worthy of the forgiveness of sins, in the manner that we encounter in Scripture those who approach him and hear the divine voice: “Your many sins are forgiven.” Had that person been worthy of approaching him, he would not have had any sins! Yet because he was a sinful man and a debtor, he received the forgiveness of his debts.

Again, listen to the words of the Lord: “I did not come to save the righteous, but sinners.” And again: “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but only those who are sick.” So regard yourself as being sinful and unwell, and approach him who alone can save the lost.

686. Another Christ-loving layperson asked the same Old Man: I want to press some Jewish wine in my presser. Is this a sin?

Response by John: If, when God rains, it rains in your field but not in that of the Jew, then do not press his wine. If he is loving-kind to all and rains upon the just and the unjust, then why do you want to be inhumane and not compassionate, rather, as he says: “Be merciful, even as your Father in heaven is merciful.”

763. A Christ-loving layperson asked the same Old Man: “God created the human person free, but he also says: ‘Without me, you are not able to do anything.’ How, then, is this freedom reconciled with not being able to do anything without God?

Response by John: God created the human person free in order that we may be able to incline toward good; yet, even while inclining out of freedom, we are incapable of accomplishing this without the assistance of God. For it is written: “It depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who shows mercy.”

Therefore, if we incline the heart toward good and invoke God to our assistance, God will pay attention to our good intention and bestow strength upon our work. In this way, both are developed, namely human freedom and God’s power. For this is how good comes about, but it is accomplished through his saints. Thus God is glorified in all and again glorifies them.

765: Question: I have a servant who is wounded with leprosy. Should I keep him or not?

Response by John: It is not necessary for you to keep him in your house; for not everyone will bear to live with him. If they could bear this, that would be a pious thing to do. Yet, you should not afflict others on his account. Instead, send him to a hospice for poor lepers, and provide for his meals and as many garments as he requires, as well as his bed, so that he is no way burdened.

Excerpted from Barsanuphius and John, Letters from the Desert: A Selection of Questions and Responses, translated by John Chryssavgis (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003)

I Shall Treat Their Wounds

7. Mary said: ‘My Son, see how I wipe the tears from my eyes.

I chafe my heart even harder,

but my mind cannot keep its silence.

Why, my Beloved, do you say “Unless I die, Adam will not be cured?”

Certainly you cured many people without suffering yourself.

You cleansed a leper, yet felt no pain- it was not your plan.

You unbound a paralytic, yet were gripped by no spasm.

With a word, Merciful One, you gave sight to a blind man,

yet remained free from suffering,

my Son and my God.’

8. ‘You raised the dead, but did not become a corpse.

You were not placed in a tomb, my Son and my Life.

Why do you say that you must suffer for Adam to be cured?

Give the command, my Savior, and he will rise and carry his bier.

Even if Adam was buried in a tomb,

you will raise him too, like Lazarus, with one word.

The entire universe serves you, the Creator of all things.

So why do you hurry, my Son? Do not rush to your sacrifice.

Do not embrace your death,

my Son and my God.’

9. ‘You do not understand, my Mother, you do not understand what I say.

So, open the gates of your mind, welcome what you hear,

and ponder within yourself what I say.

That man I mentioned, miserable Adam, so helpless,

not only physically, but also spiritually,

wanted to be sick. He did not obey me and pays the penalty.

You grasp what I mean. So, do not grieve, Mother,

but cry out, “Have mercy on Adam,

show pity to Eve,

my Son and my God!”

10. ‘Adam, helpless because of his lack of control

and his gluttony, has been carried down into the depths of Hell

and there he sobs over the agony in his soul.

Eve, who once tutored him in irresponsibility,

groans at his side. She is as helpless as he,

so that both may learn to obey the physician’s instructions.

You understand now, don’t you? You do grasp what I have said?

Shout out once more, Mother, “If you forgive Adam,

also be forgiving to Eve,

my Son and my God!”‘

11. When she heard these explanations,

the Ewe without blemish answered her Lamb: ‘My Lord,

if I ask another question, do not become angry with me.

I shall say what I feel, so I can learn from you all I want to know.

If you suffer, if you die, will you ever come back to me?

If you set out to heal Adam and Eve, shall I see you again?

I fear that you will never return from the tomb, my Son.

I am afraid and, anxious to see you,

I shall weep and cry out, “Where is

my Son and my God?”‘

12. When he heard these questions, the Lord who knows everything

even before it happens, replied to Mary: ‘Mother, be certain

that you will be the first to see me when I come from the tomb.

I shall return to reveal to you the terrible agonies

from which I freed Adam, the terrible pains I endured for him.

I shall show my loyal comrades the marks of nails in my hands.

And then, Mother, you will behold Eve,

alive, as in Eden, and you will shout with joy,

“He has redeemed my primeval parents,

my Son and my God!”

13. Be strong for a little while, Mother, and you will see how,

just like a surgeon, I strip and rush to where my patients lie.

I shall treat their wounds:

I shall cut away solid tumors with the soldier’s spear.

I shall use gall and vinegar to staunch the incision;

nails, a lancet to probe the tumor; a seamless robe to wrap it.

The cross itself I shall use as a splint.

By this you will understand and sing,

“By suffering himself, he has destroyed suffering,

my Son and my God!”

14. ‘Cast your pain aside, Mother, cast it away,

and rush out with joy. Now I am eager to bring my mission

to its end and complete the plan of the one who sent me.

From the very first, this was agreed by me and by my Father,

with the full assent of the Holy Spirit:

I would become man and suffer to redeem that who had fallen.

So, my Mother, go and deliver this proclamation to everyone:

“By suffering he shatters the one who hates Adam-

and he returns triumphant,

my Son and my God!”‘

17. Son of the Virgin, God of the Virgin, Creator of the Universe,

you suffered and you revealed the depths of your wisdom.

You know what you were and what you became.

You wished to suffer, for you judged it glorious to save mankind.

As a Lamb, you took away our sins.

Your sacrifice, our Savior, redeemed all those who were dead.

You are the one who suffers and who cannot suffer.

You save by dying! You gave your holy Mother

the privilege of faith: to cry out to,

‘My Son and my God!’

St. Romanos the Melodist (d. after 555), ‘Mary at the Cross,’ translated by R. J. Schork, in Sacred Song from the Byzantine Pulpit: Romanos the Melodist (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1995), 110-113, 114