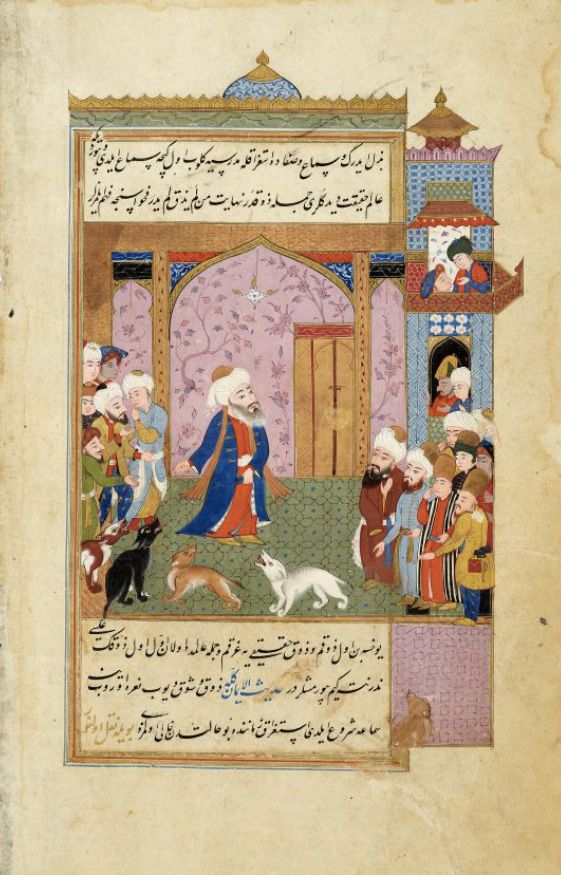

The following story hails from a massive hagiographic compilation in Ottoman Turkish, Hediyyetü’l-ihvân, written by one Mehmed Nazmî Efendi (d. 1669) and dealing with the lives of a series of saints leading up to his own şeyh (Ar. shaykh) in the seventeenth century. This story comes from the life of Şemseddîn Ahmed Sivâsî (1519-1597), who was born in the little town of Zile in Anatolia and eventually settled in Sivas, becoming in time quite well known, to the point of Sultan Süleyman the Great inviting him to go on campaign with him to Hungary. The charming tale that I have translated here points to his fame among the towns and villages of this part of Anatolia. It also reminds us of the complicated relationship between people and dogs that has historically been the case in Islamic lands: we see both an outbreak of ‘anti-dog’ measures in the person of the (unnamed and castigated) kadi, the studied ambiguity of a hadith, and the robust support of the saint, simultaneously. That a saint would intervene on behalf of unjustly treated dogs is not particularly surprising- accounts of Mevlana Rumi’s interactions, and those of his followers, with dogs circulated in the Ottoman world, as witnessed by the above illustration, contemporary in fact to this story.

![]()

From among his miracles was the following: the people of Karahisâr-ı Şarkî [modern Şebinkarahisar] sent messengers to Şems asking him that he honor them with his preaching, counsel, [performance of] zikr [1], and his blessed noble beauty. In answer to their supplication he came, and was honored immensely, being given a fine place to stay as well as much feasting and amiable conversation. For some time he preached, gave counsel, and led zikr, then announced that he was returning to Sîvâs. When the scholars, şeyhs, merchants, notables, and ordinary people of the town all came together to give him a farewell with honor and respect, numerous dogs also came before the saint, and, as if presenting complaints, began barking! When Şems asked why they were barking so, the people replied, “Because there has been plague and pestilence in our town, the kadi [2] of our town ordered the killing or banishing of the dogs, so that we killed some and we banished some. These are dogs that we banished.”

The saint cried out, “Your kadi was heedless of the hadith which says, If dogs were not a community (umma) from among the communities, then I would order them killed.” [3] Saying that, he addressed the dogs: “Go safely and soundly back to dwell and to be at rest in your former places!” As the townspeople returned from bidding the saint farewell, they saw these words fulfilled as the dogs, understanding the command, followed after the people back into town to their usual places—and having done so, by the command of God, the plague was lifted on that very day!

![]()

[1] That is, the practice of ‘remembrance (Ar. dhikr) of God’ in a ritualized manner.

[2] The kadi- literally, ‘judge,’ from Ar. qāḍī- was not just an arbitrator of legal cases but, in the Ottoman context, a multi-task administrator.

[3] The meaning of this hadith, attributed to Muhammad, seems to be that dogs have a special status as an umma, which normally means a religious community (such as the umma of all Muslims); this special status outweighs any negative aspects dogs may have.

Şeyh Mehmet Nazmi, Osmanlılarda tasavvufî hayat: Halvetîlik örneği : Hediyyetü’l-ihvân, edited by Osman Türer (İstanbul: İnsan Yayınları, 2005), 359-360. Translation by Jonathan Parkes Allen, 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.