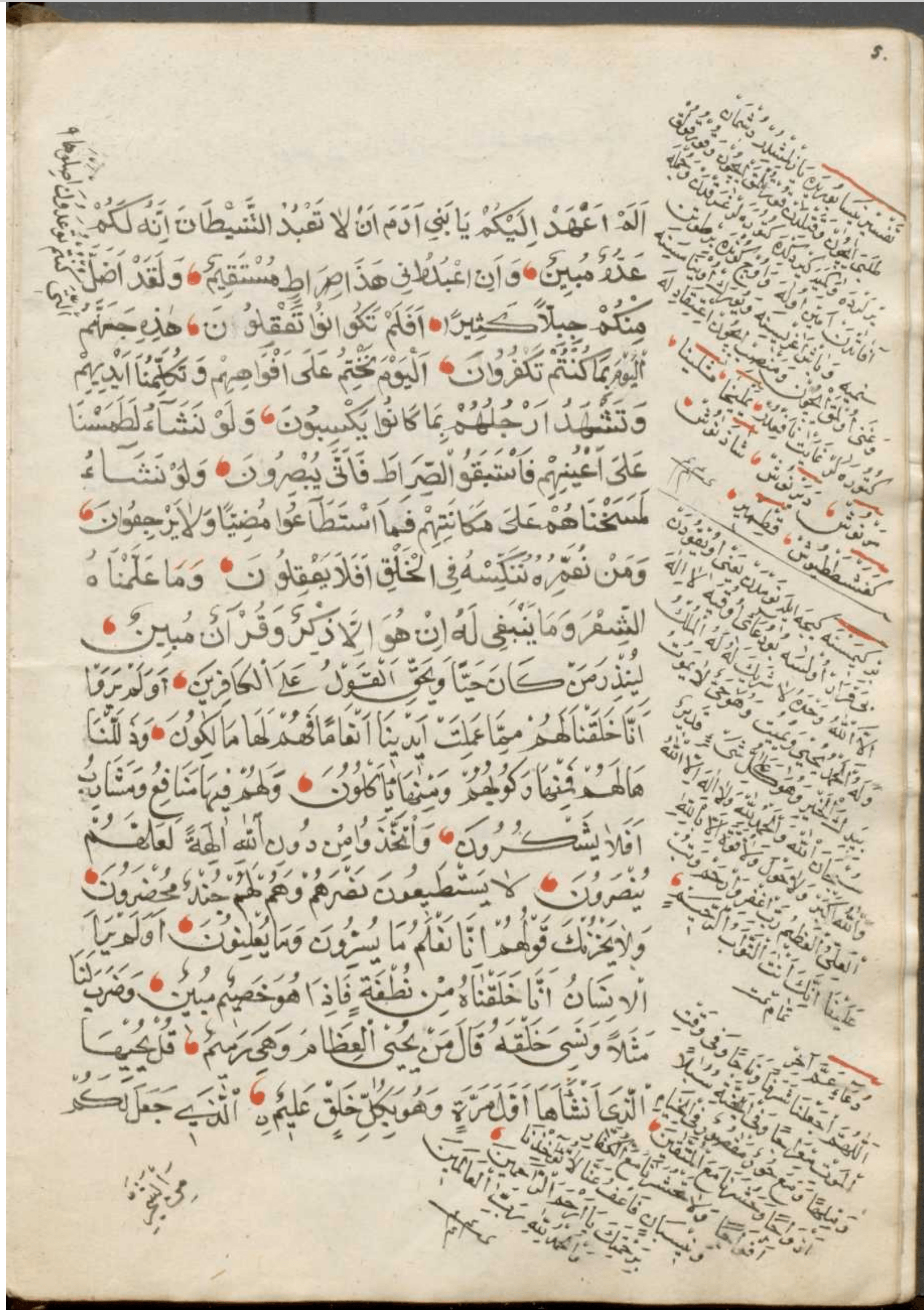

During an Islamicate manuscripts reading group I am coordinating this semester, I was looking around in my archive of digitized manuscripts for some nice examples of marginal texts and came across the manuscript from which the above image comes, a majmū’a (a collective volume of many discrete texts between two covers) of various sorts of material, produced somewhere in the Turkish-speaking part of the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century or so. As we read through some of the marginal comments surrounding this particular main text (a compilation of awrād, devotional litanies for use throughout the day), we came to the one in the top right corner of this page. Written in Ottoman Turkish, the note claims to relay information from the tafsīr of al-Nīsābūrī concerning the effaciousness of writing out the names of the Aṣhāb al-kahf, generally known as the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus in Christian tradition, which will ward off all manner of evil and bring much good. Briefly for those not familiar with the story, the ‘Companions of the Cave’/’Seven Sleepers of Ephesus’ were seven (though the number varies in pre-Islamic traditions, variance which is referenced- and not resolved- in the Qur’an) young men who fled from Roman persecution into a cave and were granted divine sleep for three hundred and nine years, awoke to find a totally transformed world in which Christianity was now dominant, disclosed themselves to the wondering population, then died. While the exact origin of the story and devotion to the Sleepers is now obscure, their hagiography circulated in numerous languages, from Sogdian to Old Irish, ending up in the Qur’an as a sizeable portion of Surat al-Kahf (‘the Cave’), alongside other material (including renderings of the names of the Sleepers, which are not given in the Qur’an).

In the marginal notation above only six of the human Sleepers’ names are given out of the usual Islamic seven (a number not however fixed by the Qur’an), plus that of their dog, Qiṭmīr, himself a de facto saint in Islamic tradition (his name has sometimes been treated as prophylactic aid on its own in fact). The notation is brief, but it got me thinking about the textual traces of the Seven Sleepers in the Islamicate world, which I’d like to explore a bit here. The use of names of the Seven Sleepers/Aṣhāb al-kahf provide a good view into the ways in which elements of ‘manuscript culture,’ of the textual materia of the book, crossed over into other media and spheres of life, parallel to the boundary-crossing nature of devotion to and the semantic traces of the Seven Sleepers themselves. As I discuss in a parallel but more philosophical and speculative essay on my Substack, there is a lot that we can continue to glean from this strange story and its incredible historical afterlives.

In Islamic contexts, devotion to the Seven Sleepers was expressed in multiple ways, but two stand out: one, the ‘finding’ and veneration of caves associated with them, to the point that caves reputed to have held the Sleepers in their several centuries of sacred slumber proliferated across the Islamicate world, from Turkestan to the Maghrib (with a similar proliferation present in Christian lands). But even more widespread were the names of the Sleepers: as with several other sites of Islamic devotion, in the general absence of pictorial icons, names and verbal descriptions served as de facto ‘icons’ reproducing the presence and the sacred power of holy figures. In the early modern Ottoman context, beyond Muhammad and his house, verbal ‘icons’ of the Four Rightly Guided Caliphs, of the Ahl al-Badr (fighters and martyrs in the Battle of Badr), and the Aṣhāb al-kahf were frequently reproduced within manuscripts and across other media, in some cases also embedded in other texts. There are no doubt many reasons for this focusing on names; in the case of the Companions/Sleepers, it is partially an inheritance of the late antique heritage, as visible in lines from the sixth century Syriac poet St. Jacob of Serug (translated here by Sebastian Brock):

There were there two wise men, sons of the leading men,

and they reckoned that the Lord would resurrect them,

so they made tablets of lead and placed them beside them,

on them they wrote down the names of the children of light…

Already there is a sense of their names having an important function, if not quite the prophylactic one they would gain in early modern Islam. By whatever routes however, those names- which as we will discuss below, were inherently distinctive just in their spelling- would be the locus of devotion and power for Islamic audiences, and traces of that devotion and power are readily visible in the manuscript tradition.

In the example below, a short poem (for those who do not read Arabic, it is the section marked with what look like red commas) off gives their names in succession and then details the particular potencies of each name when written down, either for a certain thing or upon certain media. The names of the Sleepers are written in red (fifth through seventh lines), the virtues of each then adumbrated in a series from ‘the first’ to ‘the seventh,’ the numbering also rubricated:

Early modern Islamic audiences took such messages to heart: the names of the Companions do indeed appear in many, many contexts outside of manuscripts. Here are two of them: first, a prophylactic seal made in the eighteenth century Ottoman world (Met. 1983.135.11), the text consisting primarily of the Sleepers’ names intertwined; the stamp produced by this seal could have been applied to manuscripts, or perhaps for the production of stand-alone amulets, upon documents, and so forth (perhaps even on walls, one wonders). As with many such calligraphic amuletic devices, human legibility is not primary in terms of the effectiveness of the writing; and in this case, even a cursory look at the writing suggests whose names are given here:

At the other end of portability (well, almost- obviously it was disassembled and moved at some point!) is this fireplace of Iznik tile (V&A 703-1891), built in 1731 for the home of someone quite well off indeed; the names of the Sleepers run across the very middle of the installation, the only instance of text in the entirety of the piece:

The inclusion of the names of the Companions/Sleepers on a fireplace no doubt stemmed from multiple concerns: the hearth was, and still is to some extent, a deeply resonant and powerful place in the home, even in the rarified homes of the elite; in the premodern world, the fireplace was even more central of a location as the primary source of heat in winter (which in the Turcophone tier of the empire was no small matter, particularly in the colder interval of the so-called ‘little ice age’ of early modernity). The hearth already possessed a certain degree of sanctity, as it were; the names of the Sleepers might supplement that sanctity, the hearth becoming almost a domestic qibla. Yet fire was also a source of danger, especially in the parts of the Ottoman world in which wood construction predominated; Constantinople in particular was under constant threat of conflagration. The fireplace was supposed to contain fire, but it couldn’t hurt to place in the flame’s vicinity some extra protection. Here the names of the Sleepers are meant to preserve boundaries, to prevent the transgression of limits, and so avoid catastrophic fire. Yet, I want to suggest, the power of these names lay at least in part thanks to their having crossed linguistic and confessional boundaries, standing out as other and different, akin to many holy people and places, rarified, slightly dangerous, and potent.

The names of the Seven (or less or more, the Qur’an itself is ambivalent on the question) Sleepers and their dog Qiṭmīr appear across the Islamicate textual record with a sharpness and a sense of incongruity, it is almost too perfect the way in which their awakened presence in the original story parallels their out of the ordinary semantic presence in the world of Arabic script: their names are very obviously not of Arabic- nor, somewhat less obviously, of Persian or Turkish- origin, long strings of letters in combinations unlike the overwhelming majority of words used in any of the three languages (absent the odd Greek loan here and there). Every other name rendered for prophylactic or sanctifying- in so far as we can discern a difference- purposes is solidly Arabic and Islamic, without ambiguity, but in this case the names are Islamic only by later adoption, and are not ‘Arabicized’ beyond being rendered in Arabic script. They are semantically other, and they are other in the context of the story, possessing a sort of sanctity closely akin to that of other mysterious, ecumenical figures like al-Khiḍr.

Here there is a definite proximity to what we would generally call ‘magic,’ or the ‘occult sciences,’ a diverse portfolio of practices and ideas that start to loose discursive coherence when queried too long. On the whole, however, we might say that magic exists at the boundaries of the properly religious and sanctified, that it fades into gray and darker areas, not just in terms of mechanistic processes but in terms of the powers called upon and the methods employed. Magical practices were, and are, ecumenical, not just as a matter of historical development, but as part of their internal logic. Antiquity and otherness, strangeness and distance, were built into magical practices, gave them their charge; one did not need to understand the incantations or names being used, and in fact perhaps it was better one did not. Word and power were closely linked, such that translation could undo the potency of a given talisman or spell or powerful name. Words, decomposed often times in to the even more powerful constitutive lone letters, were the principal locus of magical power, sometimes written in recognizable scripts, sometimes in mysterious ‘occult’ ones, effectively illegible without a key. The names of the Companions were rendered in Arabic script, but they partake of that visual strangeness, of a sense of distance and otherness- and therein I would suggest lies part of their power, distinctive from the other prophylactic names of premodern Islamic devotion and ritual protection.

The above has only begun to scratch the proverbial surface of devotion to the Companions of the Cave, to the presence of the Sleepers in Islamicate life and textual production- I have not consulted any early modern tafsīr, for instance, which would be an obvious and probably productive route; as time permits I will aim at translating some of the above texts in full with annotations, and hopefully supplement with some selected tafsīr. Once I do so I’ll be sure to link back to this essay- and I encourage my readers to be on the lookout for the names of the Seven Sleepers and Qiṭmīr, let me know if you find them!

___________________________

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This was an interesting read! Of what i heard , the sleepers woke up after around 300 years later. The king at that time was a noble man and had prayed to God to guide his people and waking up of the sleepers and their coming to the town/city was a glad tiding for the king. The story of the group disappearing was carried as a folk tale among the people and people recognized when the 300 old coins were presented by the sleepers to the people. And God knows best!