This post continues my three-part exploration of a short Ottoman manuscript text, Risāla fī ithbāt ruʾyat al-nabī yaqaẓatan li-man iṣtafāhu min ʿibādihi al-ṣāliḥīn, by the otherwise obscure scholar Muḥammad b. Aḥmad al-Kūmuljinawī; if you have not already read Part I much of the following will not make sense, so start there then proceed to the following.

In Part I we were introduced to the manuscript as a codicological unit, and reviewed some of the paratextual aspects that appear in this handful of folios. In the remaining pages the same elements continue, plus some additional ones, which we’ll examine before plunging into the main topic of this post, the theological content and the way in which al-Kūmuljinawī drew upon existing authorities, how he might have gone about locating sources, and what we can gather about ‘canonical’ theological authorities in the eighteenth century Ottoman world. Let’s have a look at the second page in the treatise and note the paratextual elements visible there:

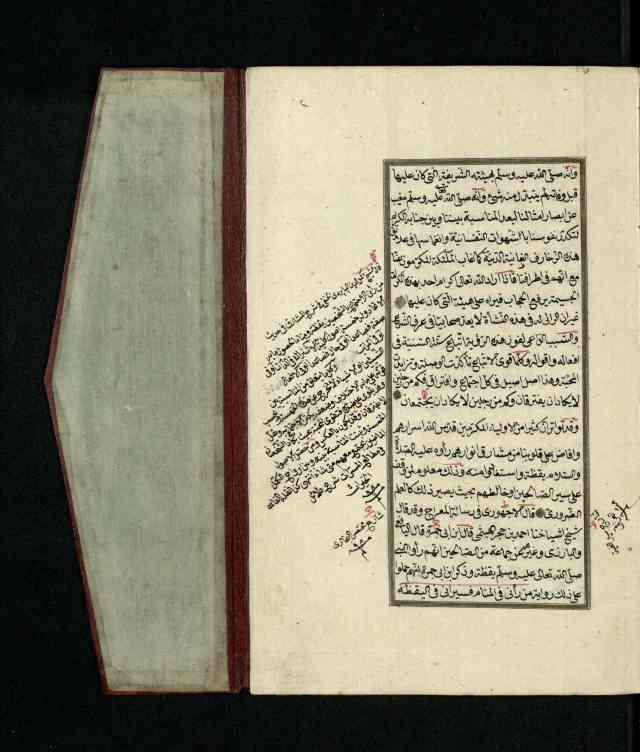

First, it’s important to pay attention to things that might otherwise fade into the background: for instance, this manuscript features a frame around the main text, a common feature but not a universal one, bespeaking the refined nature of the manuscript and its intended purpose as a presentation text. More mundanely, the frame neatly demarcates the main text from its marginal apparatus: in the case of this manuscript, primarily comments that are the functional equivalent of footnotes in modern book practice. In the example above, three annotations are visible, all examples of the minhu, ‘from him,’ type of note, placed there by the author of the text (at least in this case- in other cases the provenance of such notes can vary). The notes are linked to particular points in the main text via rubricated letters, very much akin to the footnote, although spatially they are placed more or less proximate to the linked section of main text, and hence in a variety of arrangements- an affordance of handwritten texts that is considerably more of a challenge for typography (though not insurmountable; not a few early Ottoman printed works featured sloping commentary text, though not at varying angles as here).

Nearly all of the minhu comments in this section, save a single (incorrect as it turns out!) translation of an obscure Arabic word into Ottoman Turkish, are in the same hand as the main text, which we’ve every reason to believe is the hand of the author (or, if not in his actual hand, the hand of a scribe to whom he dictated). For more on these notes and their relationship to authorship, manuscript transmission, and so forth, see A Tunç Şen’s ‘Authoring and Publishing in the Age of Manuscripts: the Columbia University Copy of an Ottoman Compendium of Sciences with Marginal Glossing.’

The other paratextual element to notice in this section of the text is the use of red overlining at various points: there is no single modern equivalent for this overlining, as at points it functions like italicizing or bolding, drawing attention to a particular point in the text; at other points it functions somewhat akin to quotation marks, or, at least, the first set of quotation marks. In the example above, the final line is largely overlined, marking out a particular ḥadīth visually from the rest of the text (in Persian texts from this period, switching from nasta’liq to naskh for ḥadīth and Qur’ān did similar visual denotation work). Taken together, all of these paratextual elements- dots, rubricated words and letters, and overlining- aid the reader in navigating and interpreting the text, knowing immediately where cited texts begin, or where important arguments or transitions are located. In my translation below I’ve largely ‘translated’ these elements into modern punctuation; on reflection I think it would be interesting to try and replicate them exactly, and will try to do in the final installment of this series.

I have aimed for a relatively literal translation, while trying to draw out some of the nuance in the usage of technical vocabulary, the most challenging aspect of this text to render in English. I initially tried a two-column display here, but found that it caused a serious error when displayed on the front page of the website, unfortunately, so I have had to drop the marginal notes down to the end of the translated section.

Know that it has been established by definite texts from among the sound and sunna-conforming aḥādith that our lord and master Muḥammad, God bless him and give him peace, is alive in his grave in body and soul, and that he has freedom of action and can go where he wills in the quarters of the earth and in the imaginal realm (al-malakūt). Verily, he—God bless him and give him peace—is [still] in his noble form in which he was before his death, nothing has been changed. And if he, God bless him and give him peace, is hidden from the sight of the likes of us, it is due to the relational distance between us and between his noble person, due to the turbidity of our lower selves due to the passions of the self and their immersion in the attachments to these trifling vain wordly babbles, just as the noble angels are hidden from us even as they are in our very midst.

Now, if God desires to honor anyone with this bodily miracle, He raises the veil and he is able to see him in his true form (this does not entail that the one who so sees him is in the ranks of the Companions in a sharī’a-accordant sense). The generative cause for the obtainment of this vision is his following the sunna in his deeds and words. The more that he strengthens his following [of the sunna] the more resilient will be his personal connection [with Muḥammad], and love [for him] will increase. This is the fundamental root of all union and separation—there are those people who are scarcely ever in a state of separation and those people who are scarcely ever in a state of union [marginal note a.].

It has been established by multiple avenues of transmission that many among the noble saints, God sanctify their inner secrets and pour out blessing upon our hearts from the orients of their lights, see him, upon him be peace and blessing, in waking life, and spiritually benefit from him—that is something that is known to the one who comes to the path of the saintly or who associates with them, such that it becomes akin to necessary knowledge.

Al-Ajhūrī (d. 1655) [marginal note b.] said, ‘The shaykh of our shaykhs, Aḥmad ibn Ḥajar al-Haythamī said that Ibn Abī Jamra [marginal note c.] said that al-Yāfi’ī and al-Bārazī and others from among the community of the saintly pious have said that they have seen the Prophet, God bless him and give him peace, in waking life. And Abū Jamra mentioned that they experienced that in accordance with the transmitted saying, “The one who has seen me in a dream-vision, he will see me in waking life.” Truly, they have seen him in dreams and they have seen him afterwards in waking life, and have asked about various things and he has reported to them concerning those things, and it has turned out as he has related to them.’

The one who denies that, if he is from among those who cast calumny upon the miracles (karāmāt) of the saints—then we have nothing to say to such a one. Otherwise, this [vision] is from among [their miracles], when in the rending of [the] customary [nature of things] there is unveiled to them things in the world above and below.

Al-Fāsī (d. 1698) says in Maṭāli’ al-massarāt [his commentary (sharḥ) on] Dalā’il al-khayrāt: ‘Shaykh Abū ‘Abd Allāh al-Suhaylī [also vocalized as al-Sahlī], God be pleased with him, has said: “In order to affix love of the Prophet in the soul, do not let his noble form be hidden from the eye of insight for a moment—it is the true vision because the vision of sight is due to his conveyance of the true essence of the one who sees to the eye [or essence] of insight, so that in the presence of insight there occurs comprehension regarding the true reality of what is conveyed to [sensory] sight from among the visible things. There is no doubt that ṣalāt upon the Prophet, God bless him and give him peace, if one’s innate disposition (mashrab) is purified, will shed forth its lights and the lower self (nafs) will become a mirror for [Muḥammad’s] form, God bless him and give him peace, and will not be hidden from it. This is true knowledge in which there is no doubt. Continue reading “Many Worlds in One Manuscript: A Close Reading of Ms. Yah. Ar. 765, Part II”